In the second of a two-part conversation with Mike Potts, CEO of StreetDrone, he lends us his thoughts on the outlook for post-Covid autonomous mobility – better, worse or just different?

Q – Mike, we spoke at some length a week ago about the outlook for post-Covid autonomous mobility, specifically about the need to remove the safety driver from an autonomous vehicle and why you think the focus should be on slow speed urban solutions, like shuttles and delivery services, as a first priority to make the commercial model work and therefore to allow the technology to scale – rather than autonomous mobility being caught up in a seemingly process wheel of test and trial. But you also hinted at another aspect to how you think this goal for slow speed urban autonomy can be accelerated. Tell us a little bit about that…

Mike Potts: Well, as we said last week, we know Waymo have raised $3bn and presumably spent a good deal more. It’s not a defensible economic analysis by any stretch, but if you amortise that across their fleet of 600 or so robotaxis, they become some of the most expensive vehicles on the planet. And in spite of that enormous capital commitment, they are, by their own admission, struggling to crack the problem of universal autonomy.

For the vast array of smaller players who might have some of the answers that Waymo are searching for, the game looks far too expensive to get involved – in other words, the barriers to entry are extreme.

When we set up StreetDrone a few years ago, we had to consider how to get involved without the luxury of billion dollar budgets. Shortly after we’d launched our first autonomous-ready vehicle, we came across an open-source self-driving project called AutoWare. We joined as a premium member and some of our team are now part of the foundation’s Technical Steering group. Where the code didn’t entirely work for our use-cases, we stripped it back, added our own code and within a short timeframe we were able to successfully operate a slow-speed autonomous vehicle. That work culminated in us running Europe’s first public road trial of an autonomous vehicle using open-source code.

What this proved was that it was possible to run an autonomous vehicle at a basic level without the need for big budgets, so as long as there is a collaborative approach to some of the technical challenges. open-source projects have this inherent strength at their core. By extension then, there is clearly more than enough engineering skill and capacity to solve some really significant self-driving challenges without the necessity to spend huge amounts of R&D dollars.

But of course this isn’t an approach that is being followed by players like Uber and the majority of the big car makers. Everyone is trying to engineer their own proprietary way to a final solution – BMW is trying to solve the same problems as Mercedes and Audi and that just doesn’t seem sensible or sustainable. It might do if it had delivered results, but the brutal reality is that the proprietary approach hasn’t worked.

Q – So what’s the alternative?

Mike Potts: Well, take a look at Linux. It depends how you measure it, but around 95% of the world’s servers run Linux open-source software. There is simply no point in Google running a different, proprietary operating system and Amazon to run another. It’s a foundational level of technology managed and developed by an open-source community of maybe 20 or 30,000 engineers. The reality is that basic the foundational level of autonomy – let’s say driving a car down the road, have it execute simple operations to turn, stop and start at low speeds can already be taken up by a mature and validated open-source layer. More sophisticated functions can evolve from this starting point.

Q – But as you’ve said, open-source has been tried before?

Mike Potts: Yes, Autoware is most definitely the closest approximation to a genuinely open code platform for autonomy. And there are others too, such as Apollo, but none of these – to extend the analogy – is really a complete proxy for what Linux is to the server market.

Why the Linux model seems like it might win out in autonomy is not only because it is supported by a great many companies and engineers but that there is a commercial layer that sits on top. These are services companies such as Red Hat, that help install Linux, build out tools and technologies that support Linux and that ensure stable, tested and validated code is available to those who wish to pay for it.

Adopting open-source for autonomous vehicles will likely need both of these components. An engine room of open code development along with the rigour and safety of a validation layer so autonomous enterprises can safely hurdle barriers to entry quickly and with minimal outlay together with a mature enterprise solution so we stay safe as we push forward.

Q – We see lots of OEMs such as Toyota and Ford offering to share data. Does this help?

Mike Potts: Well, it is positive to see a more collaborative mindset taking root for sure. The data allows everyone to see in simulation what progress is being made, but that data isn’t always deployable across platforms. We couldn’t take public domain data from Argo or Cruise and run it on our StreetDrone vehicles, so we have to distinguish between data and code – and as such, open data is part of the answer, but certainly not the most important part from what we can tell at the moment.

Q – Should everything be open?

Mike Potts: If you stop to consider for a moment how deep the stack is in the transition from ‘regular’ automotive to fully connected autonomous vehicle services, it represents a huge amount of development. That requires investment and therefore, no, not everything can or should be open.

Where I think an open approach should take precedence in areas where common standards are needed, for instance, safety – which is an easy one, or interfaces for example, so we have a common basis for vehicles to talk to infrastructure. And another area which seems counter-intuitive but actually is much better served by collaboration, is cyber-security. So from the basic self-driving code into a range of areas such as these, I firmly believe that open-source not only has a role to play, but will actually do a quicker and better job. And none of this prevents commercial enterprise sitting on top of the open foundation so businesses can earn revenue. These are not mutually exclusive aims.

Q – What types of collaborator would be needed to make an open-source approach work

Mike Potts: I think the open initiative would need to include organisations like Amazon or DHL that have a highly developed understanding of fleets operating in specific use cases. Lots of smart companies in the technology sector can provide the autonomous knowledge, but that needs to be welded to detailed insight into the domain where we want the autonomous vehicle to operate, and to interoperate – so it is not just performance on the highway but also in the logistics centre and the integrations with live delivery management.

And then of course you would need the research capabilities of leading tech universities, telecoms companies that provide the essential 5G connectivity. Companies like StreetDrone then have to knit that architectural plan together into a cohesive eco-system and build out the technical solution.

Q – And what kind of roadmap could you foresee for this kind of collaboration?

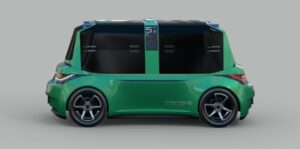

Mike Potts: Well, returning to the subject we discussed last week – slow and urban autonomy – whatever will appear on our streets has to be commercially-viable in order to be scalable – that is the inescapable hardstop for autonomous vehicles. So if you ask me to gaze into a crystal ball, I’d be saying driverless last mile delivery in urban settings travelling at slow speeds will be the first manifestation of true autonomy in the wild.

Autonomous delivery vehicles will be smaller than current delivery vans and service a smaller area. They will move slowly because there is far less premium on speed than with passenger transit – so long as your Amazon package is there when you return from work, that’s good enough, which is very different to a shuttle taking commuters to work. And while these delivery vehicles can’t of course completely prevent safety challenges to other road users or pedestrians, it remains less of a safety challenge to move ‘stuff’ at slow speeds than people at higher speed, something which adds an entirely new and expensive dimension to the safety case.

So robot delivery pods, moving slowly in our towns and cities. That’s where we are headed and it remains my conviction that this will happen quicker if we use collaboration open-source as the foundational toolkit to reach this goal.